The Motorcycle Bobber Legacy

By Ralph H. Perez

It’s 1946, and in a Southern California garage, a war veteran wrenches on a WWII-surplus Harley-Davidson WLA, stripping it to its core. Fenders are hacked off, the seat is slammed low, and the bike is reborn as a bobber. The hacksaw he used likely emerged in the early 19th century during America’s Industrial Revolution. One thin, durable steel blade and a whole lot of elbow grease were all it took.

Today, the grinder is our new hacksaw. It likely appeared when electricity became widely accessible to everyone.

This is the brief story of the 20th-century motorcycle bobber, spotlighting my recent Honda bobber Memorial Day 2025 project and BMW’s motorcycle journey from cruisers to adventure bikes to bobbers.

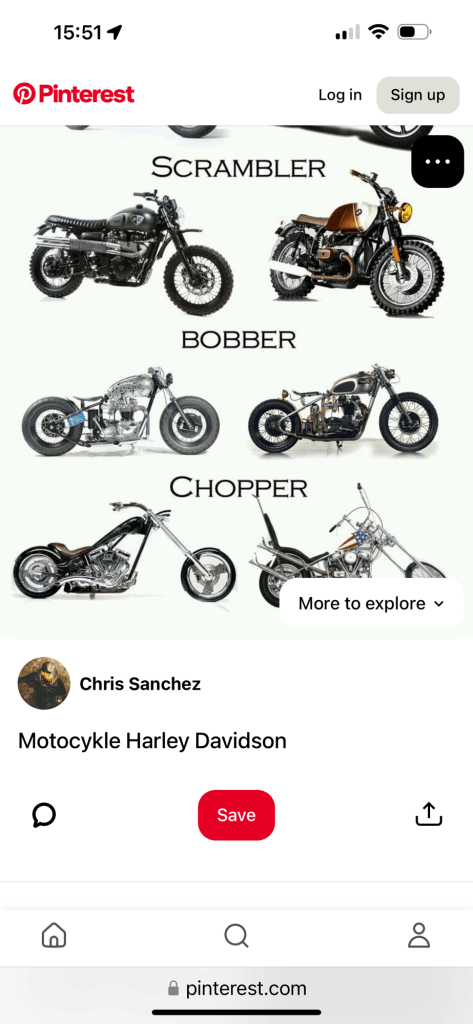

Bobbers began as a rebellion. After World War II, American veterans took heavy stock bikes—Harleys and Indians—and stripped them down for a bare minimalist look.

The term “bob-job” came from chopping parts off with a hacksaw, a nod to the 1920s when riders modified Harley J-Series V-twins for better handling.

The 1953 film The Wild One made bobbers a cultural icon. It stars Marlon Brando as Johnny Strabler, leader of the Black Rebels motorcycle gang. In the movie, they disrupt a small California town, clashing with locals and a rival gang led by Chino (Lee Marvin).

Tensions spark vandalism, violence, and a showdown with the town’s elected officials and the police, who are tasked with removing the “vermin” from the town’s boundaries. Johnny grapples with alienation at first but is quickly distracted by a fleeting romance with bad-girl wannabe Kathie (Mary Murphy), who I believe is either the daughter of the local priest or the town’s mayor. Inspired by the 1947 Hollister, California, biker riot, the film defines 1950s rebellion and the antihero archetype.

When “outlaws”—often young, disillusioned veterans or rebels—rolled into small-town USA, residents reacted with alarm. These groups, clad in leather and riding loud bikes, symbolized chaos and nonconformity. Their arrival, often during rallies or unplanned fuel stops, brought instant disruption to daily life. Public drunkenness, drag racing, and vandalism (like in Hollister, where bikers trashed a local bar) followed. Townsfolk, wary of outsiders, saw the motorcycle gangs as threats to their safety and morals. Locals sometimes confronted the gangs, leading to street brawls. Sheriffs, often outmatched, called state police for support, and towns later imposed curfews. In Hollister, 59 arrests were made over three days. Gangs embodied rebellion against post-war conformity, while towns clung to tradition, mirroring The Wild One’s tensions between Johnny’s gang and the townspeople.

The chaos was short-lived but left a lasting impression, fueling 1950s fears of juvenile delinquency and shaping the outlaw biker mythos seen in Brando’s film.

Back to the bobber: everything about it is subtraction—no fairings, no extra chrome, just the essentials. Riding open roads without a wind visor is, for me, a form of punishment. The bugs alone can bruise your face or worse.

Picture a solo saddle, a chopped rear fender, an exposed engine, spoked wheels, and a round headlight. Riders like my neighbor Jason live for this.

His 1980s Harley bobber, with its matte black tank and custom exhaust, took a year to perfect. “It’s not what you add,” he says, “it’s what you cut away.”

BMW bobbers were late to the party. Early models like the 1950s R 50 and R 60/2 were built for touring. By the 1960s, customizers eyed BMW’s airheads.

An R 50/2 bob-job kept its boxer engine’s distinctive profile—cylinders jutting out like fists—while shedding fenders and extras for a lean look. These builds were rare, as BMW’s precision engineering clashed with the bobber’s rough ethos, but the airhead’s reliability and unique stance made it a cult favorite. I’d love to own one myself.

BMW’s factory-built bobber arrived in 2020 with the R 18, a cruiser embracing bobber aesthetics. Powered by an 1802cc Big Boxer engine—the largest BMW ever made—it delivers 91 hp and 120 lb-ft of torque, blending retro style with modern tech.

The R 18’s low stance, round speedometer, and exposed engine scream bobber, with refinements like LED headlights and a partially integrated braking system.

BMW now offers a factory Bobber Kit with a flat rear-wheel cover, black number plate carrier, and solo seat, evoking the ‘40s bob-job vibe.

Older airheads, like the R 100 and R 65, also became bobber darlings.

The R 12, launched in 2024, doubled down on BMW’s bobber cred. Its 1170cc boxer engine and cruiser frame are tailor-made for mods, with options like drag bars and chopped rear trim.

Its retro round speedometer and low seat height make it a natural for bobber builds, whether in a garage or custom shop.

Bobbers, from Harleys to Hondas, evolved from home garage projects to global icons. At bike shows, an R 18 might park next to a classic R 80 bobber, each telling a rider’s story. Factory bobbers offer convenience and reliability, but modifying your own motorcycle allows unmatched personalization.

For a fraction of the cost, I transformed my 1998 Honda Valkyrie 1520cc flat-six “old man” motorcycle into what I now call my WWII touring bobber. This was my Memorial Day present to myself for my 32 years of military service. As I rolled it out of the garage, the throaty rumble of its new exhaust echoed the spirit of the post-war rebels who first stripped their bikes to the bone. Each turn of a wrench or cut with the grinder was a nod to their defiance, a tribute to the freedom they continued to chase on two wheels.

With my Valkyrie project nearly complete—still waiting for retro-style turn signals and a small welding job by my friend Jason—I took down the American flag hanging out front, hit the garage door button, and closed it.

Today, the bobber lives on—not just in showrooms or custom shops, but in every rider who dares to carve their own path, shedding what they consider unnecessary to reveal the true soul of the machine beneath.

“Memorial Day is a time to pause and reflect on the cost of freedom. As a veteran, I know the weight of that cost—it’s carried in the hearts of those who served and the families of those who didn’t come home.” —Dan Crenshaw, Navy SEAL veteran and U.S. Representative