Echoes of Old Havana: A Tale of Mojitos, Memories, and a Mother’s Wish

On the second day of my journey through Old Havana, the city unfolded before me like a faded photograph—crumbling yet alive, steeped in a past that refused to fade. I set out from my guesthouse near the Malecón, that stone ribbon hugging the sea, and wandered roughly five miles, my hiking shoes scuffing cobblestones worn smooth by decades of aimless footsteps. Walking here felt like Cuba’s national pastime—slow, deliberate, a dance with no destination. The air hung heavy with salt and the promise of rain as I crossed the Malecón, veering closer to the port where a single cruise ship loomed like a misplaced giant. The sky cracked open just as I ducked into the first shelter I could find—a small, open-air restaurant perched on a corner, its three walls little more than antique prison bars rusted by time. I slid into a wobbly chair, the downpour missing me by seconds, its roar drumming against the tin roof like a mambo gone wild.

A chalkboard menu caught my eye: two-dollar Cuban mojitos, scrawled in white loops. I ordered one, the glass arriving chilled and sweating, a sprig of mint bobbing in rum and lime. Outside, the rain painted the streets in silver sheets, trapping me in this iron-barred oasis. Five miles of wandering had left me pleasantly adrift, and now, with the storm as my captor, I settled in. At the next table sat a man nursing a mojito twice the size of mine, his dark eyes flicking toward the deluge. I struck up a conversation, as you do when time slows to a Cuban crawl. “Paulo,” he introduced himself, his Brazilian accent rolling like a samba. We traded small talk about the weather—humid, relentless—until he dropped a bombshell that turned our chat into something deeper. “I’m here fulfilling my mother’s death wish,” he said, his voice steady but tinged with something raw.

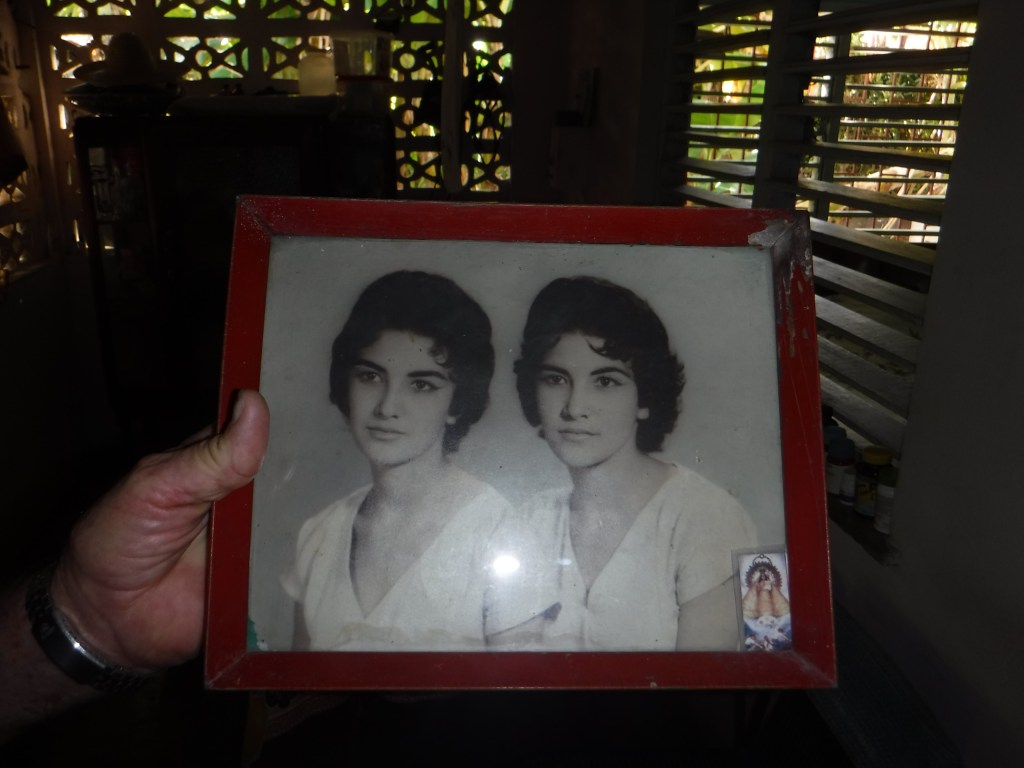

Paulo’s story unspooled like a thread from a forgotten tapestry. His mother, a Cuban by birth, had fled the island as a young woman, baby Paulo in her arms, when the revolution swept through in 1959. The family abandoned everything—home, history, hope—and rebuilt in Brazil, never looking back.

She’d spent her life in exile, her heart tethered to a Cuba she’d never see again, and made Paulo swear, time and again, that he’d return. More than that, she wanted him to reclaim his roots, to become a Cuban citizen before his own end. “She died three years ago,” he said, swirling his oversized mojito. “This is my promise kept.” I tried to imagine it—stepping onto your native soil after a lifetime away, like waking from a coma to find the world frozen in amber. Cuba, Paulo mused, was its own coma patient—stuck in a time warp where ’50s Chevys rumbled past peeling facades, where ATM machines, phone booths, and shopping malls were ghosts of a future that never arrived. “It’s like she left it,” he said, gazing out at the rain. “Like I’m a baby again, carried through these streets.”

Paulo was midway through his citizenship quest, a process as tangled as Havana’s alleys. One requirement: spend a month on the island, trouble-free, and chat up a “Yuma”—Cuban slang for foreigners like me, non-Spanish speakers from beyond the Miami bubble. “You’re my Yuma,” he grinned, raising his glass. I laughed, then frowned at my puny mojito.

“What the hell? Yours is a bucket!” Paulo chuckled, and the waiter—a wiry guy with a lazy smile—explained that Paulo had ordered off the secret, non-chalkboard menu. “Next time, amigo,” he said, winking. I waved my empty glass. “Just make sure my chicken, beans, and rice isn’t smaller than his, or Lucy’s got some ‘splaining to do!”

Blank stares. No I Love Lucy reruns here, no Ricky or Babalu to bridge the gap. It was nearing 11:00 a.m., our second mojitos in hand, the rain still pounding, and our plates nowhere in sight. “Maybe they’re chasing the chicken,” Paulo quipped, and I pictured a flustered cook sprinting through the wet streets, lasso in hand.

Over those mojitos, Paulo turned philosopher, sharing culinary tidbits that danced between absurd and profound. “Thirty thousand edible plant species on Earth,” he said, “and humans eat maybe seven in bulk.

Here? Beans, chicken, rice. That’s it.” I glanced at the menu—no fish, no shrimp, despite the sea lapping a stone’s throw away. “Can’t keep it cold,” I guessed, nodding at the bar’s ancient fridge, its hum more prayer than promise. Paulo leaned toward the waiter. “Anything from a cow?” The guy perked up. “Sí, señor.” Paulo smirked at me. “See? Speak the lingo, get the goods.” I jumped in. “I’ll have what he’s having—cow something—and throw in fried bananas.” The waiter’s face fell. “No bananas.”

An island drowning in banana trees, and none made it to this Malecón haunt. The Malecón itself—Spanish for a waterfront embankment—was Havana’s pulse, a place to stroll, sit, and sweat out the summer heat. No rules plastered the walls here, no A-B-C health grades like back home. You judged a spot by gut instinct—rodents in the corner? Food on hand?—and forgave the lack of hot water or creaky pipes. “For great Cuban food,” I muttered, “stick to Miami.”

Time in Old Havana didn’t march; it meandered. No one hunched over screens—no TVs blaring propaganda, no cell phones pinging. Just us, the rain, and the clink of glasses. Life slowed to a rum-soaked heartbeat, and I blamed the second mojito, not some femme fatale.

Paulo and I traded tales of near misses and revolutions—his mother’s escape, my own brushes with chaos. Every nation’s got its upheaval, I mused. George Washington took the Continental Army in 1775, slogging through seven years of war for a new world. Cuba’s revolution was a lightning strike—short, sharp, and eternal. Sixty years under embargo, and still, the communists hustled for profit, peddling rum and cigars to keep the lights on. Paulo nodded. “Travel’s not travel without walking—endless walking.” I agreed, quoting J. Miles: “Rum, black beans, cigars, pretty girls’ smiles, sunshine, and fat men with guitars—those come easy. Everything else? A fight.”

Our cow dishes arrived—stewed beef, tender and spiced, with beans and rice heaped beside it. No size disputes; the waiter had redeemed himself. The rain eased to a drizzle, but we lingered, sipping a third round, the bars around us dripping like wet iron lace. Paulo spoke of his mother’s Cuba—lush, chaotic, a paradise lost to politics—and I pictured her, a young woman clutching him as boats carried them to Brazil. “This place,” he said, “it’s her ghost.” I thought of today’s revolutions, beamed live on screens we didn’t have here—Putin versus Zelensky, a world braced for fallout, echoes of October 1962 when missiles loomed off this very coast. “Revolutions should tweak the system,” I said, “not bomb it to rubble.” Paulo shrugged. “Cuba’s still standing—barely.”

We paid—four bucks for my mojitos, a pittance—and stepped into the damp streets, the Malecón stretching before us like a gray ribbon under a clearing sky. Paulo had a month to survive, to prove himself Cuban. I had days left to wander, a Yuma soaking in a coma-dream island. “Simplicity and organization go far,” I said, thinking of Washington’s legacy. “Here, it’s just survival—and mojitos.” Paulo laughed, clapping my shoulder. “See you in Miami, Yuma. Bring bananas.” And with that, we parted—two strangers bound by rain, rum, and a mother’s dying wish, in a city where time stood still, whispering stories through its rusted bars.

I love that story and the memories of it still bring me back. Looking forward to a mojito soon too.

LikeLike