“We do not take a trip; a trip takes us.” — John Steinbeck

(from Travels with Charley: In Search of America, where he reflects on how journeys shape and command us, rather than the reverse).

It was still dark, cool, and overcast at around 5:00 a.m.—though my alarm was set for 6:30. Out here in the Sierra Madre Occidental, time felt irrelevant. After days on the open road, I had become something closer to a survivalist, pared down to the bare essentials.

In Walden, Thoreau distilled life to four necessities: food, shelter, clothing, and fuel. That was 1854. In 2026, riding motorcycles through remote Mexico, we quietly revised the list: staying alive on two wheels, and food. Everything truly “needed” fit into two side cases. We carry our own burdens—and often invent them.

The day before, I’d ridden the gondola deep into Copper Canyon (Barrancas del Cobre). From the heights, the landscape below was dotted with tiny figures—cattle, or perhaps people—too distant to tell apart. Clinging to the cliffs were simple structures: homes of the Rarámuri, known as the Tarahumara or “the running people.” They have inhabited these vast canyons for millennia, preserving ancient traditions amid the slow encroachment of modernity. Their endurance is legendary: running vast distances barefoot or in huaraches, often in games like rarajipari, chasing a wooden ball along treacherous paths.

Near the gondola station, I met two children—a shy 12-year-old girl and a boy of similar age. They spoke Spanish but were reserved. When I asked about school, they mentioned attending “primary school,” without mention of specific grades. It seemed education was equitable for boys and girls at that level, at least in their community. The canyon itself is unforgiving: dramatic temperature drops from day to night, scarce water along trails, and survival hinging on ingenuity and resilience. Modern touches ease some hardships—gondolas and hoists now deliver goods to isolated villages—but isolation remains profound.

This journey was never just about miles on a motorcycle; it was an adventure in the truest sense. Adventures defy itineraries—they emerge from the unforeseen, from how we confront what arises.

For Dale, it was a baffling issue on his BMW GS 1300 that turned out to be nothing more than an over-tightened zip tie. For Brian on his KTM 1290, a problem vanished only to reappear 100 miles from home, forcing a tow truck rescue.

The loneliness of those canyon outposts struck me hard. The quiet tenacity required to endure—manning remote stations against brutal weather, potential bandits, and soul-crushing solitude—felt almost superhuman. The silence here is deafening.

On our final morning before the long ride home, Mike and I hit the hotel buffet at 7:02 a.m., eager for coffee that hadn’t yet appeared. Thirty minutes later, Mike tracked down the eggs—cooked quietly in a corner by a lone attendant. Mexican families were already there, early risers claiming their included breakfast. The room rate was steep—$300 a night—but the buffet was part of it.

Even in this remote spot, smartphones dominated. People clustered where the 3G Wi-Fi was strongest: the dining area, not the rooms. The modern world seeps in everywhere, even when we seek to unplug.

Through it all, the trip was taking me—reshaping what I value, stripping away illusions of necessity, and showing that the most profound journeys unfold not on any map, but within.

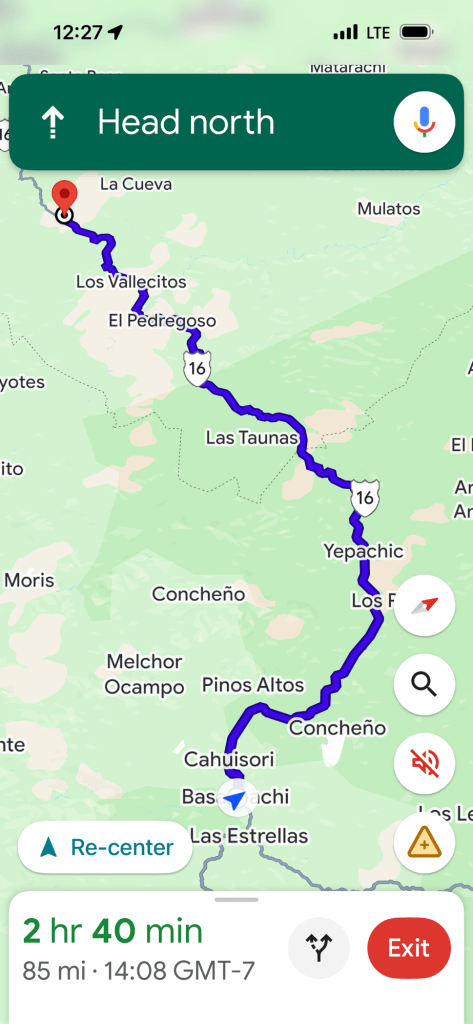

We were riding a stunning stretch of Mexican Federal Highway 16, the Carretera Federal 16, through the rugged Sierra Madre Occidental—pine forests, sheer canyons, and sparse services. The route crosses from Chihuahua near Creel (accessed via a short side road, Chihuahua State Highway 25 south from near Guerrero) westward into Sonora toward Yécora.

Key settlements along or near the highway from east to west include San Juanito (logging area near the Creel turnoff), Tomochi (historic Jesuit mission town), Basaseachi (close to the famous falls national park), Maycoba (Pima community just east of the state line, with colonial church ruins), and finally Yécora.

Today, Yécora was our lodging destination. By 8:00 a.m., we left an area near the Adventure Park and then headed towards Creel; kickstands up at 0900, everyone packed and ready.

This was to be our last day together but no one knew that this morning. Now it was just Mike and me; Dale and Todd had another 175+ miles to go to get to Hermosillo. The road here was twisty and in lots of areas dangerous for the unsuspecting. Imagine dodging potholes, lost firewood and then coming around a corner to find a longhorn steer standing on the road? And then sometime later a larger bull.

We rode west but just imagine for a moment you riding east from near the coast of Hermosillo’s sun-scorched plains on Highway 16.

The desert slowly yields—cacti fade into rolling hills, then oak woodlands, until you crest into towering pines, crisp mountain air, and misty valleys. This is where we are now for the evening. Yécora sits at about 1,576 meters (over 5,170 feet) elevation—a cool, alpine-like enclave in Sonora’s highlands, where winters bring frost (and occasional light snow), summers remain mild, and pine scent lingers in the breeze.

Founded in 1673 by Jesuit missionary Alonso Victoria as San Ildefonso de Yécora (later briefly La Trinidad), it evolved from colonial mission roots into a municipal seat in the early 20th century.

Today, this quiet town of roughly 3,000–5,000 residents (2020 census around 4,800 for the municipality, with some rural decline) lives at a gentle rhythm, sustained by forestry, ranching, small agriculture, and a modest flow of eco-tourists escaping the lowland heat.

The road had taken us far—physically across mountains, inwardly toward simpler truths. As Steinbeck knew, we didn’t conquer this trip. It reshaped us.

This is probably the last story. I’ll write about this adventure so I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did.

Ralph